Adorable Behaviorists

Little Albert was an eight month old child who briefly starred in an experiment by behaviorist John Watson. Watson showed him a fuzzy white rat. Albert seemed to like the rat well enough. After Albert liking the rat had been confirmed, Watson showed him the rat again, but this time also played a very loud and scary noise; he repeated this intervention until, as expected, Albert was terrified of the white rat. But it wasn’t just fuzzy white rats Albert didn’t like. Further investigation determined that Albert was also afraid of brown rabbits (fuzzy animal) and Santa Claus (fuzzy white beard).

I’m sure the kid turned out fine.

He put pigeons in a box that gave them rewards randomly. The pigeons ended up developing what he called “superstitions”; if a reward arrived by coincidence when a pigeon was tilting its head in a certain direction, the pigeon would continue tilting its head in that direction in the hope of gaining more rewards; when the reward randomly arrived, the pigeon took this as “justification” of its head-tilting and head-tilted even more.

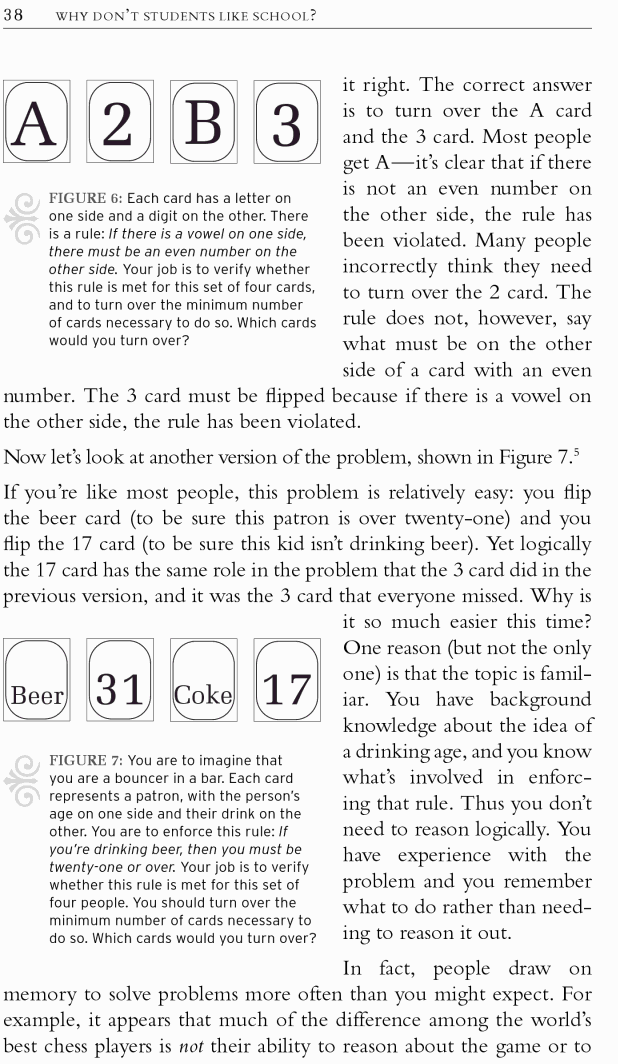

People also don’t look for negative confirmation when they’re told to learn a pattern. They usually do this poorly even when forming explicit plans (not only with automatic learning), e.g.

There are four cards which have a letter on one side and a number on the other side. I lay them out and the cards appear as 2 5 F E. The rule is that a card with an odd number on one side must have a vowel on the other. What is the minimum number of cards you should turn over to prove the rule is true (and which cards would they be)?

The “positive test strategy” is sometimes a useful heuristic, but it’s embarrassing how bad people are at escaping it (see Wason’s “confirmation bias” experiment and its Bayesian refinement).

[There is a strong] correlation between educational TV shows and so-called “relational aggression” - things like bullying, name-calling, and deliberate ostracism. The shows most strongly correlated with bad behavior were heart-warming educational programs intended to teach morality. Why?

The researchers theorize that the structure of these shows often involved a child committing an immoral action, the child looking cool and strong, and then at the end of the show the child eventually gets a comeuppance (think Harry Potter, where evil character Draco Malfoy is the coolest and most popular kid in Hogwarts and usually gets away with it, whereas supposedly sympathetic character Ron Weasley is at best a lovable loser who spends most of his time as the butt of Draco’s jokes). The theory is that children are just not good enough at the whole feedback of conseqeunces thing to realize that the bully’s comeuppance in the end is supposed to be the inevitable result of their evil ways. All they see is someone being a bully and then being treated as obviously popular and high-status.

So funny.

HT